Is it because my car is nice, clothes are nice, because I listen to Jay-Z, cuz I'm kinda cute? Or is it just "jealousy"? This has got to be the weakest emotion that anyone can have. To be jealous that I have what you don't have. But what I don't understand is why hate on just me? Then I thought, ain't no one fresher than me, no one flier than me, no one realer than me. So I am the reason people hate, prime reason you should hate anyone like me. I think it's cuz I was "BORN 2 BE HATED.”

Is it because my car is nice, clothes are nice, because I listen to Jay-Z, cuz I'm kinda cute? Or is it just "jealousy"? This has got to be the weakest emotion that anyone can have. To be jealous that I have what you don't have. But what I don't understand is why hate on just me? Then I thought, ain't no one fresher than me, no one flier than me, no one realer than me. So I am the reason people hate, prime reason you should hate anyone like me. I think it's cuz I was "BORN 2 BE HATED.”- from the diary of Rashad McCants

ON FEBRUARY 10 2004, UNC sophomore Rashad McCants entered the second half of a game against Georgia Tech having only scored three points. The Heels, struggling along with a 4-6 conference record in Roy Williams’ first year as coach, trailed by five. The half started with a quick Georgia Tech run that expanded the lead to ten.

Over the next sixteen minutes of game time, McCants put on one of the most dazzling one-man shows in Tar Heel history, scoring twenty-eight points, draining three after circus three. Unfortunately for the Heels, McCants’ performance on that night was matched by Tech’s BJ Elder, who scored twenty-four in the half, and Carolina ultimately lost the game 88-77, a star was born in Chapel Hill. But here, finally, was the remedy to the Joe Forte blues—the explosive scorer and charismatic dynamo who could lead Ol’ Roy’s Heels back to the Final Four.

Back then, when a defense of Matt Doherty was enough to start a fight at Spanky’s or Woody’s or He’s Not Here, we were desperate. Perhaps we overlooked some early warning signs with McCants. There was never any official reason behind the Doherty firing; the accepted story in Chapel Hill was that Felton, May and McCants, offended by Doherty’s suggestion that they might need a psychiatrist, incited a mutiny that cleared the way for the Roy Williams era. In retrospect, the sports psychiatrist story only seems relevant in the context of McCants.

McCants, perhaps in a first-ever in the history of lazy sportswriters using the word mercurial, actually kind of was, well, mercurial. His antics on the court were always strangely anti-Carolina. Instead of taking on any leadership responsibilities, McCants seemed to orbit around the team’s gravitational center of May, Felton and Jawad Williams—never quite engaging, but always nearby, always doing his own thing. McCants flashed the Roc-A-Fella Domination sign after dunks, he saluted the cameras, he popped his jersey and preened for the crowd. To his credit, his theatrics were acts of exultation—unlike other “emotional” players, Rashad never argued with refs, he didn’t bicker with teammates during time-outs or on the court, he was never cheap or violent. Those of us fans who count Rasheed Wallace among our all-time-favorite Heels were happy to see that Ol’ Roy hadn’t brought the stuffier parts of Ol’ Carolina Way with him to Chapel Hill.

Yet he also played with a detached, but fully-formed intensity somewhere outside the usual jocularity, sportsmanship and precision one usually associates with Tar Heel Basketball. Watching him play was sometimes like watching Mike Tyson tell a joke—you love the man, the commitment, but you sometimes wonder what the fuck might be going through his head, and if what you are witnessing is the charming mechanics of a serial masochist.

Nothing that has happened to McCants over the past few years comes as any surprise to those of us who watched his career at Carolina. College, especially college in Chapel Hill, is a cocoon. Once Rashad was fed to the wolves and every quirk, every mysterious story was exposed for what it was, once he quit being Rashad McCants: eccentric and lovable dynamo for our Tar Heels, and, instead, became Rashad McCants: public property, what would happen to him? He once equated playing at Carolina to being in jail and longed for his “freedom.” What would that freedom entail? Although nobody really talked about it, Carolina fans had already seen what was odd with Rashad.

It certainly seems telling that the last image of McCants as a Tar Heel comes right after the final buzzer sounds in the 2005 National Championship. Felton, May, Marvin and Jawad mob one another under the basket. McCants is nowhere to be found. The camera finally finds him standing alone at mid-court. He has taken off his Carolina jersey and, with a smirk, presents it to the television audience.

SOCIETY-IN-THERAPY rarely extends its graces to the professional athlete. Ricky Williams is equated to Benedict Arnold; when Milton Bradley took some time off this spring to tend to some very obvious emotional issues, sportswriters piled on the usual absurd, man-in-a-foxhole metaphors. No matter how much Zack Greinke achieves on the mound, he will always be defined by the depression that caused him, God forbid, to question if he really wanted to pursue a life as a professional baseball player.

Although our post-racial language will not allow such an easy categorization, there exists a perception of a “Black depression,” that differs from its counterpart, “White depression.” Each iteration carries its own bag of causalities and images—White depression elicits bathtubs filled with blood, minivans, Mary Kay, Sylvia Plath, Edward Scissorhands, whereas the prevailing vision of Black depression is laid out along the narratives of economic hardship, limited opportunity and the ghetto operatics that much of America uses to define the totality of the African-American experience. In neater terms: White depression is The Virgin Suicides, Black depression is the fourth season of The Wire.

It certainly doesn’t need to be said that all these differentiations are myths, and dangerous ones at that, but the way they are processed seems paradoxical to certain core American values of responsibility. Why are we quicker to forgive White athletes for lapses in mental health? Why do we turn a blind eye to Josh Hamilton’s relapse, but pile on Dwight Gooden and Daryl Strawberry? Why are there glowing Sports Illustrated cover stories about the miracle of Zack Greinke’s recovery from anxiety and depression, but none about Michael Beasley? In the most essentialist vision possible, which also happens to be the touchstone for almost all discussion of sports in America, shouldn’t America (titanic) be more willing to forgive the kid with the tough ghetto childhood than the kid who gets bored with his privileged, suburban life? Why did society-in-therapy, so eager to embrace everyone that it produced a show about a mob boss and his psychiatrist, create a state of exception for the Black athlete?

Perhaps, ironically, it is exactly the self-evidence, and, in some ways, the simplicity of the causality of Black depression that creates the very narrative used to dismiss it. Because Black depression, again speaking in as essentialist terms as possible, is perceived as being the result of economically depressed living conditions, whereas White depression is written off as chemical imbalances, treatable by any number of medications, when a Black male becomes a visibly wealthy member of society, he is subjected to this catastrophic logic: Because he is rich now, the reasons for him being depressed are now gone. Therefore, he should no long show any symptoms of any mental health problems. If he does, he is simply not appreciating what he has been given.

In his pre-draft interview with the Miami Dolphins, Dez Bryant was asked if his mother was a prostitute and if she “still did drugs.” When brought in for a workout with the 49ers, Matthew Stafford was asked to discuss his feelings about his parents’ divorce. When he said he wasn’t going to talk about it, the 49ers brass downgraded him on their chart.

What is the expected answer? What could Matthew Stafford have said to convince Mike Singletary that he was mentally healthy? How was Dez Bryant supposed to react to a stranger asking him if his mother was a drug addict/prostitute? It is impossible to believe that anyone, much less a front-office employee of a professional sports franchise, could make a determination of psychological health based on these sorts of scattershot, shock-jock questions. So why ask them? What Superman is being constructed? And what, for fuck’s sake, do we expect Superman to say?

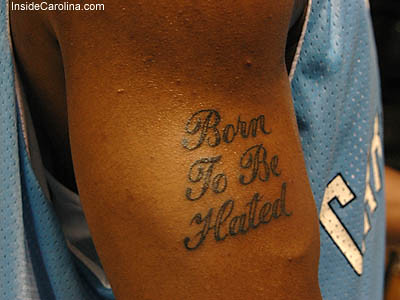

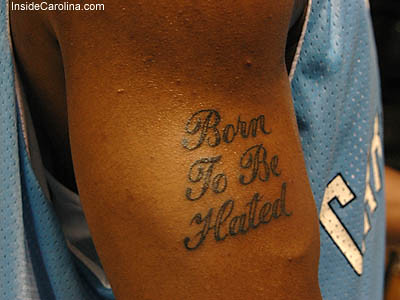

Even if we do not know, exactly, who Superman is, we know who he is not, and he is not Rashad McCants, or any of his looks of exasperation, disinterest or anger. He is not the tattoos he sports on each arm: “Born to be Hated,” and, “Dying to be Loved.” He is not the poetry McCants has written or the mostly unexplained hiatus he took from that 2005 championship team. HE is not his moodiness or his outbursts. In fact, the only NBA-ish thing Rashad McCants has done in the five years that have passed since he left Carolina, was briefly date a Kardashian.

IT IS NO SECRET THAT THE NBA has lost its personality. In this post-Gil-era, the mold of NBA superstar is more blank, unobtrusive and corporate-friendly than it’s ever been. Kids no longer run up and down the court with a specific player’s demeanor in mind, but rather, professional basketball has become a TV show in which every character aspires to be the bland, beautiful straight man. Of the top ten players in the league, only Kobe has a distinct personality, a set of easily codified traits that define who he is. What, really, do we know about Dwight Howard? When he came into the league, he was a shy, Christian kid who was so naïve that he once said that there should be a crucifix on the NBA logo. Now, he is Dwight Howard, smiling, corporate superman, stripped, with Mao’s efficiency, of any religious ornamentation. Howard’s quirks are so calculated, predictable, that he comes across as a gigantic Katy Perry. Kevin Durant is celebrated for his candor, but only in contrast with the clamminess or meanness of his fellow players Dwyane Wade is not much more than a collection of commercials, post-hipster glasses and velveteen suits. As for the league’s self-appointed King, part of the shock and rage over Lebron’s Decision Summer came from the fact that we are simply not used to such disturbances of our expected boredoms, especially from a guy who has Jordan-monotoned the cameras since his freshman year in high school. Even his recent twitter vendetta seems staged—the virtual flailings of a desperate, and, ultimately, blank man.

While it’s undeniable that a culture of sameness has arrived, one has to wonder if this is a product of the league’s relentless push into international markets (strip the game of the “Americanness” that might offend people in Europe and Asia, and watch it grow!), or if it is truly a reflection of something much more ominous: a society that has built up an industry of mental health to tamp everyone down into a docile vessel. Is there so much difference between McCants and Charles Oakley? Is he more polarizing than Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf? The NBA once was a place where volatile personalities were used as weaponry—players like Lambeer, Oakley, Mahorn, Andrew Toney and Mourning played not so much as individuals on the court, but as embodiments of their unchained egos.

What I am trying to ask is this: in the arena of sports, are we still willing to accept eccentricity?

FREE RASHAD is for all of us head-cases, the misunderstood. It is for all of us who wanted to walk the earth with Ricky Williams, for those of us who listen to Mike Tyson and see a vision what we might be like if we had lived through a similar chaos. It is for those of us who, like Rashad, have never quite been able to bridge the gap between our conception of self—no matter how catastrophic it may be—and the functioning world. It is not as much a movement to get Rashad McCants back in the NBA, as it is a lament for the league we have lost. We accept, as Rashad has, his shortcomings as a teammate, as a basketball player. We are not even saying that if we were the GM of a team, we would give our hero a spot on the roster. Rather, we ask for the league to FREE RASHAD in the hopes that it will restore a coliseum of volatility, a celebration of the eccentric, and, perhaps, in turn, delay the ever-expanding norm of the corporate, World-Wide National Basketball Association.

FREERASHAD! FREERASHAD! FREERASHAD!