Monday, August 30, 2010

hiatus

other projects are taking up too much of my time. Will resume Free Rashad when the Carolina season starts up in November.

Thursday, August 26, 2010

Sunday, August 22, 2010

This is part two of a series of thoughts on Mike Tyson. Part one is below.

II

All sports are marketed to children, or, when applicable, the child within us. What gets targeted, though, is not really childishness, but, rather, the happier approximation of childhood: the same wide-eyed kid who collected baseball cards, who wore his favorite player’s jersey, who practiced the commercialized cross-over in the driveway. The narrative of each game, season, series and franchise, then, is told as a children’s story, with simple delineations between good and evil, hero and monster. At first read, both humanity and inhumanity are assumed—as children, we do not question Grendel’s monstrosity or Beowulf’s intentions or humility. It is only later, as adults, when we can see a bit of ourselves in Grendel, that we ask questions, stitch together justifications and alter the shape of the narrative.

Similarly, our childhood sports heroes rarely hold up against time—Mantle staggers off, bottle in hand; we find Tiger balls-deep in a porn star; Jordan is off abusing dealers at the craps table; Clemens cockwalks around, needle stuck in ass. Our monsters are forgiven for their perceived monstrosities—Ted Williams’ dickishness is forgotten, Jim Brown is lionized, Ron Artest goes from “dangerous” to “quirky.” At some point in the near future, Pete Rose will record his blustery, apologetic confession on SportsCenter and baseball will determine that he is sincere and we will see him next at Cooperstown, where a gallery of fans will give him the longest standing ovation in the history of Upstate New York.

Only Mike Tyson, heavyweight champion of the world, convicted rapist and lowbrow comedy star, exists outside of these normalizing trends. It has been eight years since his last meaningful fight. The generation of kids who know Tyson as the tiger owner in The Hangover have excised him from the images we have of Mike Tyson in a grey suit and handcuffs, the images of Tyson with his arm around Robin Givens, staring incredulously as she details her daily terror. Most of us old enough to remember these things have also forgotten them. This in itself does not deviate from the normal trend of forgetting and time-fueled redemption, but what’s odd about Tyson is just how quickly we have forgotten and how the process of forgetting has not just obliterated his indiscretions, but also his triumphs.

The completeness of this evacuation of Mike Tyson’s history must be attributed, at least in part, to the violence of boxing itself. It’s hard to ratchet a man’s legacy to images if those images involve him brutally beating another man. Even the sport’s most iconic image—Muhammed Ali standing over Liston—only passes because we cannot see Liston’s face. So, yes, given the particular brutality of Tyson’s early string of KOs, it’s understandable why there is not much in the way of a visible record—we can watch Kirk Gibson limp around the bases or Dwight Clark leaping into the air, arms outstretched, but we cannot watch Marvis Frazier’s eyes get knocked out of their sockets without thinking there might be something wrong with us.

And yet, we keep him around, not as a flawed, great man whose story awaits its epilogue, but rather as a cautionary tale against our peculiar American excesses. Because this particular cautionary tale is told in a child’s terms, and because we have known about Tyson for decades now, the details of his past greatness are no longer necessary to define—just as the Emperor is simply the Emperor and Job is described as nothing more than an “upright man who feared God,” Tyson's legacy, long since stripped of its triumphant images (what would those even have been?), has been laid flat with non-evocative, ultimately inert words. All that's left, really, is a video game and the title of former champ. The spectacle of his downfall has already been dissected and discarded, plucked of its easiest metaphors and life lessons. All that’s left is Tyson, himself, and the fact that he fell from great heights down into unimaginable suffering. And just as God used Job to prove man’s resilience and faith, perhaps Tyson stays in the public’s eye because he signifies the grotesque side of that devotion to life, that indomitable spirit.

Watching him give interviews, listening to his conception of pain, hearing his contrition over his past life, brings to mind something somebody once said about JD Salinger, that he lived his life with his eyes a bit too wide open to the suffering of the world. Indeed, Salinger, a devoted Zenny man, devoted much of his post publishing career to trying to understand the first of the Four Noble Truths: All Life is suffering. For Tyson, who seems to be borne of that same handicap of over-seeing, there is no escape to New Hampshire and once God makes his point, there will be no cessation of suffering and a restocking of his riches. Where could he even go for peace?

Friday, August 20, 2010

This is the first part of a multi-part essay on Mike Tyson.

I

At the age of ten, after successfully clunking through Minuet in G at the Josiah Haynes Elementary’s annual piano recital, my parents walked me out to their station wagon. A box whose size I knew too well was sitting in the back, disguised, uselessly, really, in silver wrapping paper. There was a small rectangular tumor poking out at the top of the box and for a second, I panicked, before recognizing the shape of the growth. As it so happened, on that day, I was not to be disappointed, as the box, indeed, was the box for a brand new Nintendo Entertainment System and the tumor was a game: Mike Tyson’s Punch Out. In some bizarre occurrence that has been obliterated by the collective nostalgia for these 8-bit moments, my NES did not come with Duck Hunt or Super Mario Brothers. Instead, it came with a glossy, 200 page strategy guide for all the games that I did not own.

For the next three years, my parents steadfastly refused to buy me any more games. By the time I inherited the collection of a friend’s brother whose mother had had enough, I could beat Mike Tyson’s Punch-Out three times through without ever getting hit. My mastery of the game was so complete that it began to take on a hard-Zen aesthetic edge that lost touch with the usual demands of that virtual world—there are moments, even now, when I wonder if there truly is a way to get through the entire game without any damage. The mahareshi who stands in the way of that perfection is Great Tiger—there is simply no way to get past him without blocking his infamous, and comically ineffective spin punch. Every time you block a punch, a tiny sliver of health is sacrificed and the dream of perfection is shattered.

I have always maintained that Mister Sandman is the toughest motherfucker in the game. Again, I do not speak from the perspective of someone who is ever afraid of losing, or even really being hit more than once. Rather, once one has mastered Mike Tyson’s Punch-Out, the measurement of difficulty comes from randomness. Mike Tyson himself is completely predictable—the only hairy moments in the Dream Match come at the start of the second round, when Mike comes out and just starts jabbing. Mister Sandman, with Juan Manuel Marquez’s sleight of hand, will sometimes slip in a random jab. There were times when I would play the entirety of the game, smashing fools, cursing at the impossible riddle of Great Tiger, and as I advanced as steadily and confidently as Ender Wiggin, I would be aware of a dread forming at the back of my head: will Sandman throw in that jab?

I only mention all this because I recently noticed something odd—as a child, when I battled Mike Tyson at least once a day, when his name was always around and his 8-bit image was burned into my brain, I never really thought of him as anything but the anti-climactic end to the only video game I owned. And yet, I wonder if all those encounters with Mike, the uncharted space he inhabited in the still-hazy spaces of my “virtual” life, were unconsciously soliciting my sympathies (how do you not sympathize with a man whose ass you kick on the daily?). Because now, at the age of thirty, my once legendary Punch-Out skills long gone (I can’t even get past Soda Popinski anymore—although, officially, I blame the controller), there is never a time when I think about sports without thinking about Mike Tyson. He has become the touchstone for everything—this blog, for example, while being about Rashad McCants and misunderstood athletes, is really about Mike Tyson, because there’s no way for me to understand Rashad McCants without first referencing Mike Tyson.

I don’t think it’s much different for any of us who were born between 1970-1985. Tyson was the dominant champion of our childhoods, the hero who evoked terror in our parents, the one athlete who begged the question: how can an invincible man be so complicated? And after it began to all unravel in that bout in Japan (here’s a testament to Tyson’s wild popularity at the time—even the who beat him got his own video game), he became the enduring and incalculably tragic figure of our young adulthoods. Whenever he shows up on television, whenever some talking head or talk show radio host dismisses him as a “nutjob” or a “madman,” I experience a spike of emotion that far exceeds the appropriate limits of what a sports figure should inspire in a grown man. Absurdly, I feel the need to protect Mike Tyson, the same man who destroyed Leon Spinks in 91 seconds, the same man who I knocked out every single day of my childhood.

Labels:

glass joe,

mike tyson,

nintendo,

punch-out,

rashad mccants,

von kaiser

Thursday, August 19, 2010

Tuesday, August 17, 2010

Why does Happy Gilmore Exist?

“I am not a role model,” while an admirable sentiment, was always beside the point. Sure, parents should never raise their kids in the image of a man who has done nothing but grow really tall and ball really well, but, over the years, I’ve come across enough bad parents to fill a Tolstoy novel (I worked for a while as a teacher at a private school, in San Francisco, no less), and have never met one who pointed at Stephen Curry or Ronnie Lott or even Kurt Warner and said, “Son, live your life as he does.” It’s possible, I suppose, that Charles did help vacate some vague responsibility for athletes, but whenever I hear someone call up to a sports talk radio show and bitch and whine about how some athlete is making it tougher for the caller to raise his kids (a funny paradox: anyone who calls into a sports talk radio show should not have kids to raise…We’ll pass the verdict on pretentious basketball bloggers later), I never really believe him. In that scenario, it’s always clear that the caller who worries about his children simply sees something ugly in the athlete that he can identify in himself, and, therefore, questions his own ability to raise his kids (half the time, I don’t even believe the caller has kids at all and is just evoking “the kids,” Helen Lovejoy-style just to bask, at least for a little while, on the stoic, macho, Bro-han side of things). Nothing else makes sense.

On a somewhat related note, I have found myself wondering over the past few years why there have never been any real changes to my list of favorite athletes, only minor renovations and rearrangements—McCants replaces Vernon Maxwell, Rasheed and the Glove swap places and then swap back. And while I won’t bore you with my own personal exodus in the years that have passed since I saw Rasheed strolling around the courts at Granville Towers, just know, those traits of dysfunction that made me identify with him have all been rationalized away and suppressed, as has the dickish bravado that turned Sam Cassell into one of my heroes. Still, even after watching both those guys play out an entire career, the guys who have lined up to replace Rasheed and Sam-I-Am are just Rasheed and Sam-I-Am all over again.

During the World Cup, my least favorite player was Uruguay’s Diego Forlan. I was in Mexico City and had caught La Seleccion fever (Uruguay was in the same group with my two rooting interests: South Korea and Mexico), but I didn’t have the same problem with Luis Suarez or equally obnoxious strikers on other squads. After Uruguay beat La Seleccion, it became clear that I hated Diego Forlan because I hated his stupid face and that goddamn hair. It doesn’t need to be said that any hatred of face and hair is racialized, especially on a stage like the World Cup, and I was in the company of one of my favorite people in the world, a man who does not apologize for always rooting for the underdog: racial, civic, economic or otherwise, and it felt right to root against the blonde, attractive guy.

I think the sports talk radio caller exists on the other side of the spectrum, not politically, exactly, but in how he processes the athlete. When confronted with a “troubled” athlete, some of us root for him because we can identify the same traits in ourselves and want to see an example of society’s acceptance, but also because we want to cut down the guy who is ahead of us in the pecking order. When that usurpring desire gets too uncomfortable, the tendency is to flush out that discomfort with liberal sentiment, all of which serves to prove that while we might hate Diego Forlan because of his stupid face, we are not racist. The talk show radio caller has the same experience of identifying the trouble within himself, but instead of washing out the resulting ethical discomfort with liberal sentiment, he simply closes his eyes and identifies with the man in charge, the man who always smiles, prints money and worries about the welfare of women and children, the man who, of course, is not him.

Monday, August 16, 2010

In the Foxhole

For the professional athlete, no sin compares to the sin of being a bad teammate. It is a flattening, thoroughly destructive label to carry, and, as was discussed yesterday, its truth is completely unknowable. In a league filled with criminals, pastors and family men, all of whom are millionaires, one’s commitment to one’s team is, in some ways, the only way to delineate the good from the bad. This paradox, where the lines that divide are also unknowable and disseminated in vagaries and hearsay, brings up a litany of obvious, and, somewhat silly panoptic metaphors. Once he is tagged as a bad teammate, the athlete, despite the ability to access the media, is helpless, especially when his former teammates, fearing they, too, might get tossed into the bad half of a “divided locker room,” acquiesce and tow the company line.

Consider Ray Lewis, who, despite being acquitted of murder charges, has never been able to muster up a clear picture of what happened in that nightclub. Outside of Peyton Manning, there is no player in the NFL more lionized than Lewis. It seems as if in the estimation of sportswriters, fans and talking heads, Lewis’ very public displays of good-teamsmanship supersede any doubts about his bad-humanness. Similarly, when Kobe was perceived to be a bad teammate, whatever happened or did not happen in that hotel in Colorado was still relevant. Once Mitch Kupchak picked up Pau Gasol and the Lakers won the title, leading to an outpouring of Kobe-Gets-It speak, he was recast as a different sort of machine—the Kobe we had known, the one who was so singularly focused on excellence, had evolved into a Kobe who understood the joy of helping others. All was forgiven. When the sports world brought out its biggest stick to beat down Selfish Lebron, the most commonly evoked foil was Kobe.

Again, our military metaphors are to blame. Within the dying animal that is our macho sports culture, being a bad teammate is akin to ditching your squadron in a foxhole. In real foxholes, a lack of cooperation leads to death, and so, as long as the trust between men is assumed, one can conceivably turn a blind eye towards the indiscretions of his brother. In the military, such logic is necessary, and, I suppose, in sports, the comparison is apt, at least to a point. For any group of men to cohere into one unit, the paramount value that must be established is teamwork towards a common goal.

The logic we assume, then, goes like this: personal problems only hurt you, even if they hurt others, they only hurt the people you hurt. However, if you abandon the team, you are not only hurting all your teammates, individually, but you are spitting on the democratic ethic that binds us all together. If we draw out the military metaphor to its logical end, what we are saying is this: bad teammate, what you are spitting on is America. And in America, treason is punishable by hanging.

I must admit, despite my inclination to say something damning about this sort of logic, there’s part of me that actually agrees with it. Outside of our allegiances to others and our commitment to a common goal, how, exactly, do we redeem ourselves? I’ve long maintained, mostly for the sake of barroom conversation, that if I was presented with two people: one who stabbed someone and one who serially cuts in line, and was asked to blindly choose one of them to be my friend, I would, without hesitation, choose the stabber. There are reasons to stab someone—maybe the victim invaded your home or threatened your kids—but there is no part of my brain that can understand or empathize with someone who continually cuts in line. His heart is the uglier one because it shows no concern for anyone but himself, and, in the process, pisses all over the unspoken contract about lines: hey, we are going to stand here and we will eventually get to the front as long as nobody cuts.

I do not mean to say that being a bad teammate is somehow worse than beating your wife or shooting someone outside of a club. Such calculations are absurd and generally irrelevant. But, I will say this: there is a cleaner logic to being a good teammate. The sin does not have the capacity to carry any mitigating factors. (even if you hate the coach and organization, you should still be a bro) As such, the violations of good teammate-ness (or line-cutters) dredge up an easily categorized, clearly distilled disgust. And if this question could be somehow abstracted from its many historical contexts, and if we weren’t talking about a game played by oftentimes disinterested millionaires to boost the profile of billionaires, I might even be inclined to agree: treason is the worst sin.

But because we rely on the mainstream media to tell us who is a good teammate and who is not and because these designations fluctuate wildly and seemingly on a whim (if Lebron had stayed in Cleveland, would those Adrian Woj stories have come out? All that stuff about him being a terrible teammate is reported as fact, and yet, it took Lebron acting like an ass for it to come out that he, in addition to being basketball’s Kanye, is also a bad teammate), and because of the justifiably huge sway it has on our opinions of a man, it seems catastrophically foolish to believe anything anyone says about whether someone is a good or bad teammate.

And yet, I still believe that Rashad was a bad teammate in Minnesota and Sacramento, and somehow, it still matters. I guess my need to impose myself and my morals onto the projected image of a basketball player trumps my understanding (opinion, really) that the metaphors and logic are both catastrophically dumb.

Does that side--the one that's really about me--ever lose?

Sunday, August 15, 2010

The Captain and Rashad

Off-court issues aside, there are a lot of similarities between Stephen Jackson and Rashad McCants. Neither guy ever breaks a smile on the court. Their images are both a bit skewed by a public that wants to watch their athletes express themselves through joy. Both guys are hated in the cities they left behind. Both take ill-advised threes and have been accused of hogging the ball.

The comparison is interesting because it exposes just how fickle, specious and arbitrary our impressions can be, especially when they are distilled through what we see in a televised game. While one could match up Stack Jack and Rashad along cosmetic lines—scowling, yelling at teammates, pouting on the bench—the truth about both players gets expressed somewhere we cannot quite see. Captain Jack is one of the most beloved players in the league. His coaches drool over his competitiveness, his leadership and the way he picks up his teammates. None of that is evident to the television audience. Conversely, McCants can’t even get a phone call from Carolina guys like Larry Brown and George Karl.

And yet, if one is to trust the mega story on McCants in ESPN the Magazine, McCants’ exile is predicated largely on his body language and the strange faces he makes while playing.

What, exactly, is the difference between the two? I have no doubt that the difference is real—again, this project is not a fansite for McCants, but rather, a fansite for what McCants means—but it does confirm what we probably already knew and what the hundreds of post-Decision Lebron articles all argued. We, as fans, really have no idea what these guys are like. The ultimate teammate is the same guy who almost got kicked off an Olympic team that was created in his image. The same frowning guy who threw haymakers in the Palace and got himself arrested on a gun charge, is, in fact, the best teammate in the league, while the other frowning guy, who has never been in trouble and won a National Championship, is absolutely toxic. We cannot see these things as fans, and yet all of us, myself heartily included, keep trying to figure the shit out. When we are right, we are randomly right, and when we are wrong, we are randomly wrong.

Lastly, you must read this.

Saturday, August 14, 2010

Who Will He Be?

In recent interviews, Rashad McCants has said he would like to return to the league as a sixth man. While it's impossible to tell if this is the modest ambition of a humbled man, or, if Rashad is snake-charming us again, the possibilities of Rashad-as-bench-scoring-dynamo seem to match up with the best scraps of hope we have left for the man and his game.

He is, at times, a preternaturally gifted scorer. He can defend, when motivated. A bench role with the right coach, in the right system, with the right veteran leadership, could channel his particular brand of intensity into a dynamic weapon. But where? And, more importantly, if he did come back, who would he be?

Over the next few days, I’ll weigh some options for Rashad…

OPTION ONE: NEW YORK KNICKS

The Roger Mason signing complicates this a bit because it gives the Knicks two shooters at the off-guard position. (Azubuike is the other) Still, assuming that he would come back into the league as a role player, the Knicks seem like an ideal fit. His offensive game would flourish in D’Antoni’s system, he would be reunited with Ray Felton (who knows if that’s a good thing, though) and he would have Anthony Randolph around as a foil in temperament.

There’s an argument to be made that Rashad shouldn’t be in New York, but let’s remember, the man has never been in trouble with the law or been at the center of any sort of off-court controversy. Also, the Marshawn Lynch theory that pro athletes are more prone to get into trouble in boring towns keeps proving itself over and over again.

Most importantly, playing in the Garden would allow Rashad to channel the man he was in a past life.

John muthafuckin’ Starks, baby!

Could any of us hope for anything better than Rashad going to New York, honing all that volatility into competitiveness and becoming the second coming of #3? He and Starks are almost the same height and build. They play at a similar speed. McCants is a better shooter than Starks ever was. Starks had more bounce. The real thing that separates them is that Starks had an entire lifetime of being overlooked to burn off as motivation. McCants, in the terms of the basketball world, had everything given to him: freshman starter at Carolina, National Championship, first round draft pick. Now that the months out of the league have dragged out into years, could he dig deep and find that Starks-intensity? Could he build himself back up from fallen Carolina blue-blood (sorry) into Starks 2, self-made man?

Friday, August 13, 2010

Ask the Dust

One thing I’d like to add to yesterday’s thoughts: part of what the McCants story appealing is the character of its redemption. No story is more satisfying than the troubled, talented man who makes good, at least for a little while. Sure, the league is stocked with those sorts of stories—Kobe, in some ways, is an example—but for the balance to continue between the Howards and the Captain Jacks, there needs to be some cast-aways to redeem. My concern is that there simply aren’t any around anymore—that they have been erased from the league, replaced by a mostly anonymous army of D-Leaguers, cast-aways and mid-major stars. Yes, these men have their own Kurt Warner-themed redemption story, but what we applaud in them is simply the triumph of good, hard work. Their score is translated out into dollar signs, scoring averages. And, at some level, while we might tell our children about those redeemers, their stories are mostly interchangeable, inert.

Although I admit my Carolina fandom might be intruding, I simply cannot find a better story for redemption--emotive and basketball--than Rashad McCants, a bright, extremely talented dude who is clearly battling with some self-destructive impulses. We can rarely turn ourselves away from the wreckage of such young men, especially those who only live to deny the evidence. McCants is brash, arrogant, petulant, and, without any doubt, a horrible person to work with. He is like every writer I’ve ever met. And while I certainly don’t mean to promote writers-as-humans, (God help me, if I did) there is part of McCants’ story—he is a self-proclaimed poet—that reminds me, too much, of those haunted, hell-bent men who narrate all my favorite novels. He is going nowhere fast. He is successful with women. He alternates between hostility and overflowing generosity. We know his end is coming and that it probably won't be pretty.

He is the young narrator in Knut Hamsun’s Hunger, the NBA’s version of John Fante’s Arturo Bandini. These conflicted, wildly charismatic and destructive men all find, in some way, their redemption, and we read books because we are helpless against our sympathies. The NBA is not so much a sport as it is a clash of outsized and comical narratives. On that stage, where jocks rule the day, how can you not root for Bandini?

Thursday, August 12, 2010

Mission Statement

Free Rashad will be updated frequently and will usually be about basketball. The RSS is at the bottom of the page. Please add it to your feed.

FREE RASHAD

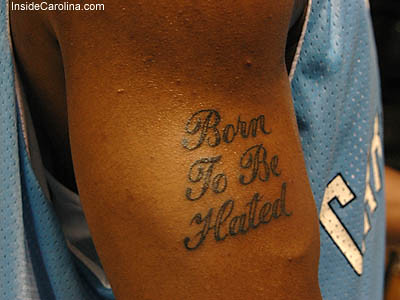

Is it because my car is nice, clothes are nice, because I listen to Jay-Z, cuz I'm kinda cute? Or is it just "jealousy"? This has got to be the weakest emotion that anyone can have. To be jealous that I have what you don't have. But what I don't understand is why hate on just me? Then I thought, ain't no one fresher than me, no one flier than me, no one realer than me. So I am the reason people hate, prime reason you should hate anyone like me. I think it's cuz I was "BORN 2 BE HATED.”- from the diary of Rashad McCants

ON FEBRUARY 10 2004, UNC sophomore Rashad McCants entered the second half of a game against Georgia Tech having only scored three points. The Heels, struggling along with a 4-6 conference record in Roy Williams’ first year as coach, trailed by five. The half started with a quick Georgia Tech run that expanded the lead to ten.

Over the next sixteen minutes of game time, McCants put on one of the most dazzling one-man shows in Tar Heel history, scoring twenty-eight points, draining three after circus three. Unfortunately for the Heels, McCants’ performance on that night was matched by Tech’s BJ Elder, who scored twenty-four in the half, and Carolina ultimately lost the game 88-77, a star was born in Chapel Hill. But here, finally, was the remedy to the Joe Forte blues—the explosive scorer and charismatic dynamo who could lead Ol’ Roy’s Heels back to the Final Four.

Back then, when a defense of Matt Doherty was enough to start a fight at Spanky’s or Woody’s or He’s Not Here, we were desperate. Perhaps we overlooked some early warning signs with McCants. There was never any official reason behind the Doherty firing; the accepted story in Chapel Hill was that Felton, May and McCants, offended by Doherty’s suggestion that they might need a psychiatrist, incited a mutiny that cleared the way for the Roy Williams era. In retrospect, the sports psychiatrist story only seems relevant in the context of McCants.

McCants, perhaps in a first-ever in the history of lazy sportswriters using the word mercurial, actually kind of was, well, mercurial. His antics on the court were always strangely anti-Carolina. Instead of taking on any leadership responsibilities, McCants seemed to orbit around the team’s gravitational center of May, Felton and Jawad Williams—never quite engaging, but always nearby, always doing his own thing. McCants flashed the Roc-A-Fella Domination sign after dunks, he saluted the cameras, he popped his jersey and preened for the crowd. To his credit, his theatrics were acts of exultation—unlike other “emotional” players, Rashad never argued with refs, he didn’t bicker with teammates during time-outs or on the court, he was never cheap or violent. Those of us fans who count Rasheed Wallace among our all-time-favorite Heels were happy to see that Ol’ Roy hadn’t brought the stuffier parts of Ol’ Carolina Way with him to Chapel Hill.

Yet he also played with a detached, but fully-formed intensity somewhere outside the usual jocularity, sportsmanship and precision one usually associates with Tar Heel Basketball. Watching him play was sometimes like watching Mike Tyson tell a joke—you love the man, the commitment, but you sometimes wonder what the fuck might be going through his head, and if what you are witnessing is the charming mechanics of a serial masochist.

Nothing that has happened to McCants over the past few years comes as any surprise to those of us who watched his career at Carolina. College, especially college in Chapel Hill, is a cocoon. Once Rashad was fed to the wolves and every quirk, every mysterious story was exposed for what it was, once he quit being Rashad McCants: eccentric and lovable dynamo for our Tar Heels, and, instead, became Rashad McCants: public property, what would happen to him? He once equated playing at Carolina to being in jail and longed for his “freedom.” What would that freedom entail? Although nobody really talked about it, Carolina fans had already seen what was odd with Rashad.

It certainly seems telling that the last image of McCants as a Tar Heel comes right after the final buzzer sounds in the 2005 National Championship. Felton, May, Marvin and Jawad mob one another under the basket. McCants is nowhere to be found. The camera finally finds him standing alone at mid-court. He has taken off his Carolina jersey and, with a smirk, presents it to the television audience.

SOCIETY-IN-THERAPY rarely extends its graces to the professional athlete. Ricky Williams is equated to Benedict Arnold; when Milton Bradley took some time off this spring to tend to some very obvious emotional issues, sportswriters piled on the usual absurd, man-in-a-foxhole metaphors. No matter how much Zack Greinke achieves on the mound, he will always be defined by the depression that caused him, God forbid, to question if he really wanted to pursue a life as a professional baseball player.

Although our post-racial language will not allow such an easy categorization, there exists a perception of a “Black depression,” that differs from its counterpart, “White depression.” Each iteration carries its own bag of causalities and images—White depression elicits bathtubs filled with blood, minivans, Mary Kay, Sylvia Plath, Edward Scissorhands, whereas the prevailing vision of Black depression is laid out along the narratives of economic hardship, limited opportunity and the ghetto operatics that much of America uses to define the totality of the African-American experience. In neater terms: White depression is The Virgin Suicides, Black depression is the fourth season of The Wire.

It certainly doesn’t need to be said that all these differentiations are myths, and dangerous ones at that, but the way they are processed seems paradoxical to certain core American values of responsibility. Why are we quicker to forgive White athletes for lapses in mental health? Why do we turn a blind eye to Josh Hamilton’s relapse, but pile on Dwight Gooden and Daryl Strawberry? Why are there glowing Sports Illustrated cover stories about the miracle of Zack Greinke’s recovery from anxiety and depression, but none about Michael Beasley? In the most essentialist vision possible, which also happens to be the touchstone for almost all discussion of sports in America, shouldn’t America (titanic) be more willing to forgive the kid with the tough ghetto childhood than the kid who gets bored with his privileged, suburban life? Why did society-in-therapy, so eager to embrace everyone that it produced a show about a mob boss and his psychiatrist, create a state of exception for the Black athlete?

Perhaps, ironically, it is exactly the self-evidence, and, in some ways, the simplicity of the causality of Black depression that creates the very narrative used to dismiss it. Because Black depression, again speaking in as essentialist terms as possible, is perceived as being the result of economically depressed living conditions, whereas White depression is written off as chemical imbalances, treatable by any number of medications, when a Black male becomes a visibly wealthy member of society, he is subjected to this catastrophic logic: Because he is rich now, the reasons for him being depressed are now gone. Therefore, he should no long show any symptoms of any mental health problems. If he does, he is simply not appreciating what he has been given.

In his pre-draft interview with the Miami Dolphins, Dez Bryant was asked if his mother was a prostitute and if she “still did drugs.” When brought in for a workout with the 49ers, Matthew Stafford was asked to discuss his feelings about his parents’ divorce. When he said he wasn’t going to talk about it, the 49ers brass downgraded him on their chart.

What is the expected answer? What could Matthew Stafford have said to convince Mike Singletary that he was mentally healthy? How was Dez Bryant supposed to react to a stranger asking him if his mother was a drug addict/prostitute? It is impossible to believe that anyone, much less a front-office employee of a professional sports franchise, could make a determination of psychological health based on these sorts of scattershot, shock-jock questions. So why ask them? What Superman is being constructed? And what, for fuck’s sake, do we expect Superman to say?

Even if we do not know, exactly, who Superman is, we know who he is not, and he is not Rashad McCants, or any of his looks of exasperation, disinterest or anger. He is not the tattoos he sports on each arm: “Born to be Hated,” and, “Dying to be Loved.” He is not the poetry McCants has written or the mostly unexplained hiatus he took from that 2005 championship team. HE is not his moodiness or his outbursts. In fact, the only NBA-ish thing Rashad McCants has done in the five years that have passed since he left Carolina, was briefly date a Kardashian.

IT IS NO SECRET THAT THE NBA has lost its personality. In this post-Gil-era, the mold of NBA superstar is more blank, unobtrusive and corporate-friendly than it’s ever been. Kids no longer run up and down the court with a specific player’s demeanor in mind, but rather, professional basketball has become a TV show in which every character aspires to be the bland, beautiful straight man. Of the top ten players in the league, only Kobe has a distinct personality, a set of easily codified traits that define who he is. What, really, do we know about Dwight Howard? When he came into the league, he was a shy, Christian kid who was so naïve that he once said that there should be a crucifix on the NBA logo. Now, he is Dwight Howard, smiling, corporate superman, stripped, with Mao’s efficiency, of any religious ornamentation. Howard’s quirks are so calculated, predictable, that he comes across as a gigantic Katy Perry. Kevin Durant is celebrated for his candor, but only in contrast with the clamminess or meanness of his fellow players Dwyane Wade is not much more than a collection of commercials, post-hipster glasses and velveteen suits. As for the league’s self-appointed King, part of the shock and rage over Lebron’s Decision Summer came from the fact that we are simply not used to such disturbances of our expected boredoms, especially from a guy who has Jordan-monotoned the cameras since his freshman year in high school. Even his recent twitter vendetta seems staged—the virtual flailings of a desperate, and, ultimately, blank man.

While it’s undeniable that a culture of sameness has arrived, one has to wonder if this is a product of the league’s relentless push into international markets (strip the game of the “Americanness” that might offend people in Europe and Asia, and watch it grow!), or if it is truly a reflection of something much more ominous: a society that has built up an industry of mental health to tamp everyone down into a docile vessel. Is there so much difference between McCants and Charles Oakley? Is he more polarizing than Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf? The NBA once was a place where volatile personalities were used as weaponry—players like Lambeer, Oakley, Mahorn, Andrew Toney and Mourning played not so much as individuals on the court, but as embodiments of their unchained egos.

What I am trying to ask is this: in the arena of sports, are we still willing to accept eccentricity?

FREE RASHAD is for all of us head-cases, the misunderstood. It is for all of us who wanted to walk the earth with Ricky Williams, for those of us who listen to Mike Tyson and see a vision what we might be like if we had lived through a similar chaos. It is for those of us who, like Rashad, have never quite been able to bridge the gap between our conception of self—no matter how catastrophic it may be—and the functioning world. It is not as much a movement to get Rashad McCants back in the NBA, as it is a lament for the league we have lost. We accept, as Rashad has, his shortcomings as a teammate, as a basketball player. We are not even saying that if we were the GM of a team, we would give our hero a spot on the roster. Rather, we ask for the league to FREE RASHAD in the hopes that it will restore a coliseum of volatility, a celebration of the eccentric, and, perhaps, in turn, delay the ever-expanding norm of the corporate, World-Wide National Basketball Association.

FREERASHAD! FREERASHAD! FREERASHAD!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)